You grew up in northern Italy, right? How did you get into music?

Yes, in Veneto and Padua, close to Venice. I started playing drums when I was nine years old. Later I got into alternative guitar music, played in different bands and then moved quite organically into the engineering direction, recording demos and mixing live sound. After school I worked in a club just outside Padua, where many experimental, weird bands stopped by at the time.

What drew you into the engineering aspect initially?

My dad used to be an electrician, and he had a little workshop in the back of the house. As a kid, I often went there to dismantle devices. I wasn’t making my dad happy. (laughs) But I had a good inclination for problem solving. When it comes to recording, there’s always something to fix, and I was pretty good at that – fidgeting around with gear, trying to understand how it works and how to make it sound better. It was also just fascinating to me to document sounds. It’s like taking a picture of a specific moment. If we record on another day, in a different mood, the result is going to sound different.

How did you become a part of the early neoclassical scene?

Well, I had a studio in Bologna for seven years. I was a recording engineer, but also touring with my own band and making records. In 2005, I met Dustin O’Halloran when he came to my studio and we started collaborating. At that time the whole ‘neoclassical’ scene just started – Dustin put out his first solo piano album, as well as Chilly Gonzales; Volker [Hauschka] was working with prepared piano, and I constantly ran into him in the most bizarre places. I was also doing sound for the composer Peter Broderick, and Nils Frahm was opening up for him at the time. We became friends, and I got to work on many projects on the Erased Tapes label.

Why did you make the decision to come to Berlin in 2011?

When we closed our studio in Bologna, I worked in different studios as a freelance producer and engineer. Actually, I think it was Nils who convinced me to come to Berlin. Dustin had moved to Berlin in the meantime as well. I had a few connections there and it sounded like a good option. I was hired to mix the first A Winged Victory For The Sullen album. I mixed it in Italy, then Dustin suggested I come to Berlin to work on it there. When I came to Calyx studios, we put the tape in the machine, and the machine blew up. Bo, the studio owner, was like: “Oh my god, we have to call the technician. This is going to cost us a week.” And I was like: “I don’t have a week. Let me try and fix it.” So I called a friend who was familiar with these tape machines, opened it, found the problem and fixed it. Bo was pretty impressed with me, so when I moved to Berlin, I started working at Calyx.

What projects did you work on in those early Berlin years?

Almost right away I got this gig with Modeselektor. I mixed their 2011 album “Monkeytown” in my car. You know, there’s a saying that all sound engineers check their final mix in the car, but I just mixed it right there, on a laptop and a mini-jack going into my car audio. I was sitting in the parking car at night, my face lit up from the computer screen. People were passing by, asking themselves: What is this guy doing? But it actually worked really well, and that led to many other projects.

How did your style change over the years since then?

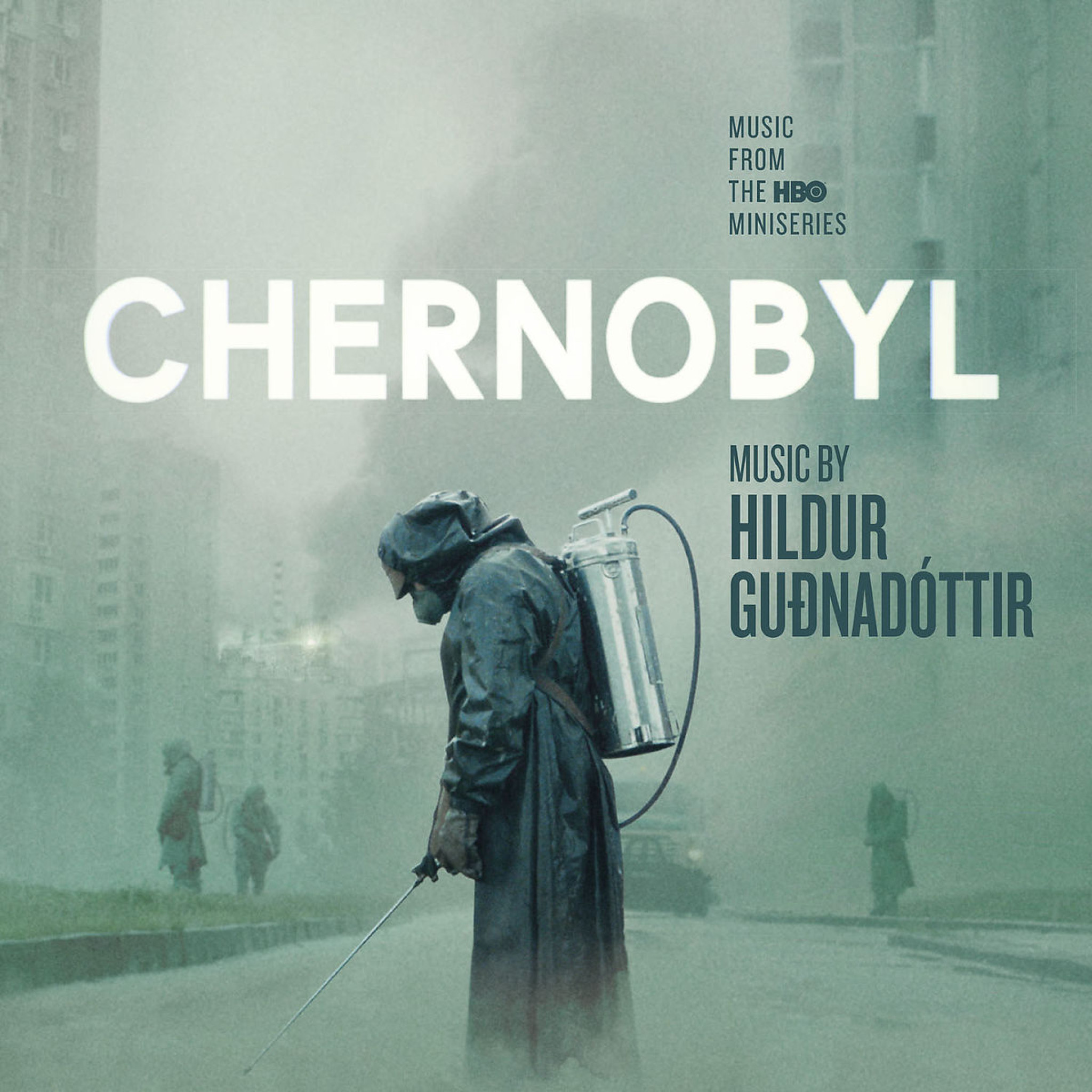

It changed from being about documentation into creating something tailored to the artist, not just like a document or a photograph, but more like a fantastic, abstract dream. I remember recording an album with Hildur. She was playing cello live in the studio and had a pedal board to trigger some pre-recorded chords. My idea was to record the sound of the room with her playing the pre-recordings through the speakers, instead of recording them straight from the computer. I spent some time on the right setup, and then she did this perfect first take. I remember sitting in the control room by myself and feeling that I was witnessing something really special.

You’ve worked with Katy Perry on the one hand, and on the other hand with Ben Frost. Do you have to be a fan of the artists you're working with?

I'm a fan of the artists’ dedication. Sometimes I'm a fan of the music as well, even most of the time. But lately, it’s been more important for me to work with true artists. I like artists that will be artists no matter the outcome in terms of fame or notoriety or money. If I feel that, it’s not even important what kind of music the artist makes. I might work on a pop record, even if that’s not something I’m very familiar with.

How do you go about finding out what the artist needs from you?

It's all about creating a connection with them, understanding what they want and how I can contribute to it – how to make it more understandable as a musical message. Some artists, especially composers, have their ideas, but they don’t express them to anyone else. But it might be good to bounce your ideas off other people to get some feedback and a deeper understanding. I offer that support to artists by providing my point of view, which comes from a certain experience.

So you’re not too interested in working with people who just want to create nice little platitudes for lean-back streaming playlists?

I have a story for you. So this artist calls me – he wants to work with me and record in my studio. He asks me if I have an upright piano. I say no, I do have a grand piano, but no upright. So he gets back to me saying: Well, I composed this music on a grand piano, but my record label asked me to record it on an upright with felt, because then I’d have more chances at ending up in one of these playlists. And I was like: This is just so sad.

What do you like about working with Hildur Guðnadóttir? Your collaboration on several soundtracks has led to some prestigious awards for both of you.

Hildur and I are at a point where we don't even need to talk about things anymore. She knows what she wants, and I know how to get there. She always has ideas that I completely follow and trust. She knows how to restrain herself and what a certain score might need, from a compositional point of view. Often she’s limiting herself to a specific set of elements, and she won’t add anything else if it’s not substantial to her vision. And if the composition is not there yet, she’ll work on it instead of just adding elements.

You’ve worked with Rick Rubin a couple of times. How did that happen?

That started when Rick was working on a record with Italian artist Jovanotti in Tuscany. They were looking for someone to mix a specific song. Rick is actually a big fan of Erased Tapes, and Lorenzo [Jovanotti] knew that I worked for them, so he asked me if I wanted to give it a try. Later I found out they had a couple of engineers mixing the same song for a blind test, and apparently he picked mine. The next time I was in Los Angeles, we hung out at his house in Malibu. We stayed in contact; I recently helped him find some instruments for the studio he set up in Tuscany and recommended an artist for his festival. Sometimes I’d get a question from him or a link to a song, and he’d ask for my opinion. One time he called me and asked if I was in L.A., because he needed someone to record a choir for Kanye [West]. At the time, he was doing the Sunday Services, and the hip-hop engineers apparently had no experience with that. It was quite intimidating, but I was busy on some other project in Berlin.

Interview: Stephan Kunze