For this latest instalment of our film soundtracks series, we have picked some of the most beloved soundtracks from some of the world’s greatest film composers. In most cases, the films are every bit as iconic as the scores, with both winning or being nominated for various global awards. There are many more we could have included; these are simply some of our favourites rather than an exhaustive list.

Max Steiner, Gone With The Wind (1939)

Austrian Max Steiner was Hollywood’s most groundbreaking composer during the 1930s and 1940s, crafting music for major films such as King Kong, Casablanca and The Big Sleep that featured the trademark leitmotifs (for both characters and settings) that gave his work such emotional depth and coherence. The score for Victor Fleming’s Gone with the Wind—created while Steiner was drastically overworked—was one of the first to utilise a full symphonic score, and drew on the music of the Civil War era, including many Southern folk melodies, helping audiences empathise with the emotional journey of the characters as well as the turbulent era.

Bernard Herrmann, Psycho (1960)

American composer Bernard Herrmann is another pioneer who worked on legendary soundtracks for the likes of Orson Welles (Citizen Kane) and Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver). He’s probably best-known for his Alfred Hitchcock scores, including Vertigo, The Birds and North by Northwest. None of them quite reached the extremes, or the fame, of the work he did on Psycho, though, which is known the world over for its dissonant chords, piercing string and rhythmic intensity. Fun fact: Hitchcock wanted to leave the famous shower scene unscored—until he heard Herrmann’s slashing violin glissando, which has gone on to become a quintessential horror movie sound.

Henry Mancini, The Pink Panther (1963)

One of the most influential and versatile film composers of the twentieth century, Henry Mancini blended jazz, classical, and pop elements to create playful, catchy and yet sophisticated soundtracks. He worked on classic movies such as Breakfast at Tiffany's (which included his song, “Moon River”), Charade and The Party. Arguably his greatest moment, though, is The Pink Panther, especially the theme track, whose smooth, saxophone-driven jazz melody quickly became synonymous with bumbling detective Inspector Clouseau (Peter Sellers), and helped inspire several sequels and a TV series.

John Barry, Goldfinger (1964)

Britain’s John Barry wrote the music for Oscar-winners such as Dances with Wolves, Out of Africa and Midnight Cowboy. He also scored 11 James Bond films after delivering some top-notch arrangements for Dr. No in 1962. Famous for subsequently infusing the 007 films with his dynamic mix of bracing brass, seductive jazz, and stirring strings, it was the third Bond film, Goldfinger, that became the first massive hit. The brass-filled title song performed by Shirley Bassey set the tone for the soundtrack—which, aptly enough, sold enough copies to hit gold.

Ennio Morricone, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Italian composer Ennio Morricone is synonymous with Spaghetti Westerns, a genre for which he broke new ground by incorporating a panoply of interesting additional sounds to his orchestral compositions: whips and gunshots, whistles and church bells, mouth organs and distorted vocals. Although the maestro only received his first Academy Award at age 90 (for The Hateful Eight), his legacy is immense, not least his scores for Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, the theme tune for which—along with “The Ecstasy of Gold”—is as iconic as they come.

John Williams, Star Wars (1977)

Probably one of the most famous film composers on the planet, John Williams is known for his sweeping orchestral scores and soaring melodies. Inspired by classical luminaries such as Stravinsky, Holst and Strauss, his works are these days played in concert halls around the world. Although he has scored some of the most iconic films to date—Schindler’s List, Jaws, Indiana Jones, E.T. and Jurassic Park just to mention his Spielberg films—we chose Star Wars; not only because the main theme is one of the world’s most memorable cinematic tunes, but because Williams stuck with the project, delivering the music for almost all of the sequels.

Vangelis, Bladerunner (1982)

Greek composer Vangelis (Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou) started out as a self-taught musician playing in Greek rock bands. He became known in the film world thanks to his Oscar-winning soundtrack for 1981’s Chariots of Fire, which remains synonymous with the Olympic games and athletic sports. But it was his work on Ridley Scott’s sci-fi cult classic Blade Runner that made his name as a real innovator. Set in a futuristic Los Angeles and starring Harrison Ford and Rutger Hauer, the film’s eerie synth-based sound matched the bleak, rain-filled dystopia perfectly, landing Vangelis BAFTA and Grammy nominations.

Hans Zimmer, Gladiator (2000)

German composer Hans Zimmer needs no introduction. Across his forty-year career, he has scored over 150 feature films, won two Oscars as well as four Grammys, and regularly packs out arenas with full orchestral shows. Whether it’s Batman or Interstellar, he has a remarkable ability to capture the emotional depth and drama of a film with soundtracks that feature strings, brass, percussion and synthesised electronics. We’ve chosen his score for Ridley Scott’s Gladiator as it was one of his early breakthroughs, and although it didn’t win an Oscar, it remains an epic soundtrack for a blockbuster movie.

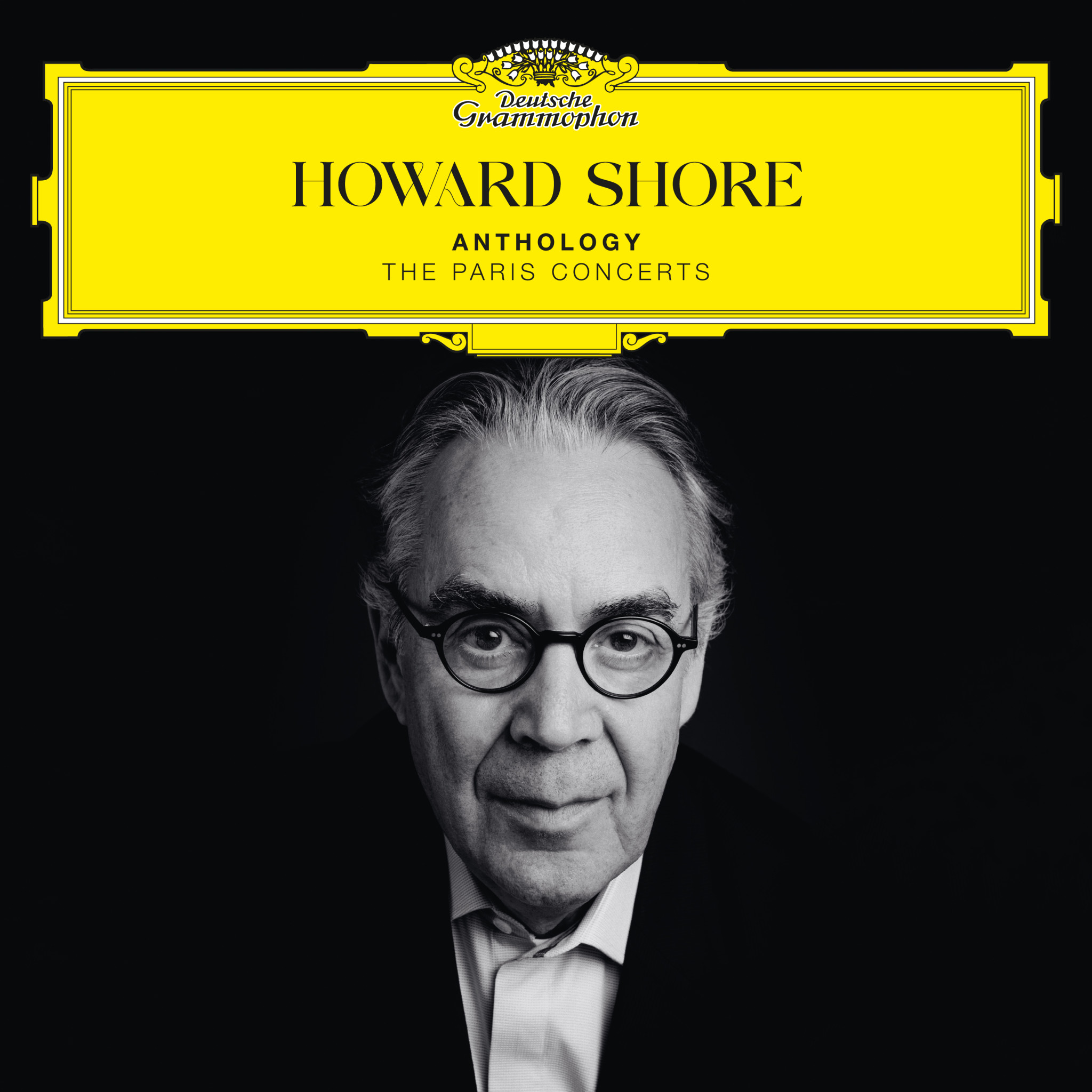

Howard Shore, The Lord of the Rings (2001)

Canadian Howard Shore's score for The Lord of the Rings trilogy is rightly considered a masterpiece of modern soundtrack work. It cannot have been an easy task, after all, to capture the epic scale and yet minute detail of Tolkien's world. But by skilfully blending orchestral grandeur—complete with choirs and solo voices—with dozens of recurring leitmotifs, Shore’s sonic tapestry manages to roam effortlessly from doom-laden dissonance to gentle, bucolic passages, and is every bit as rich and enjoyable as the film itself.

Words by Paul Sullivan