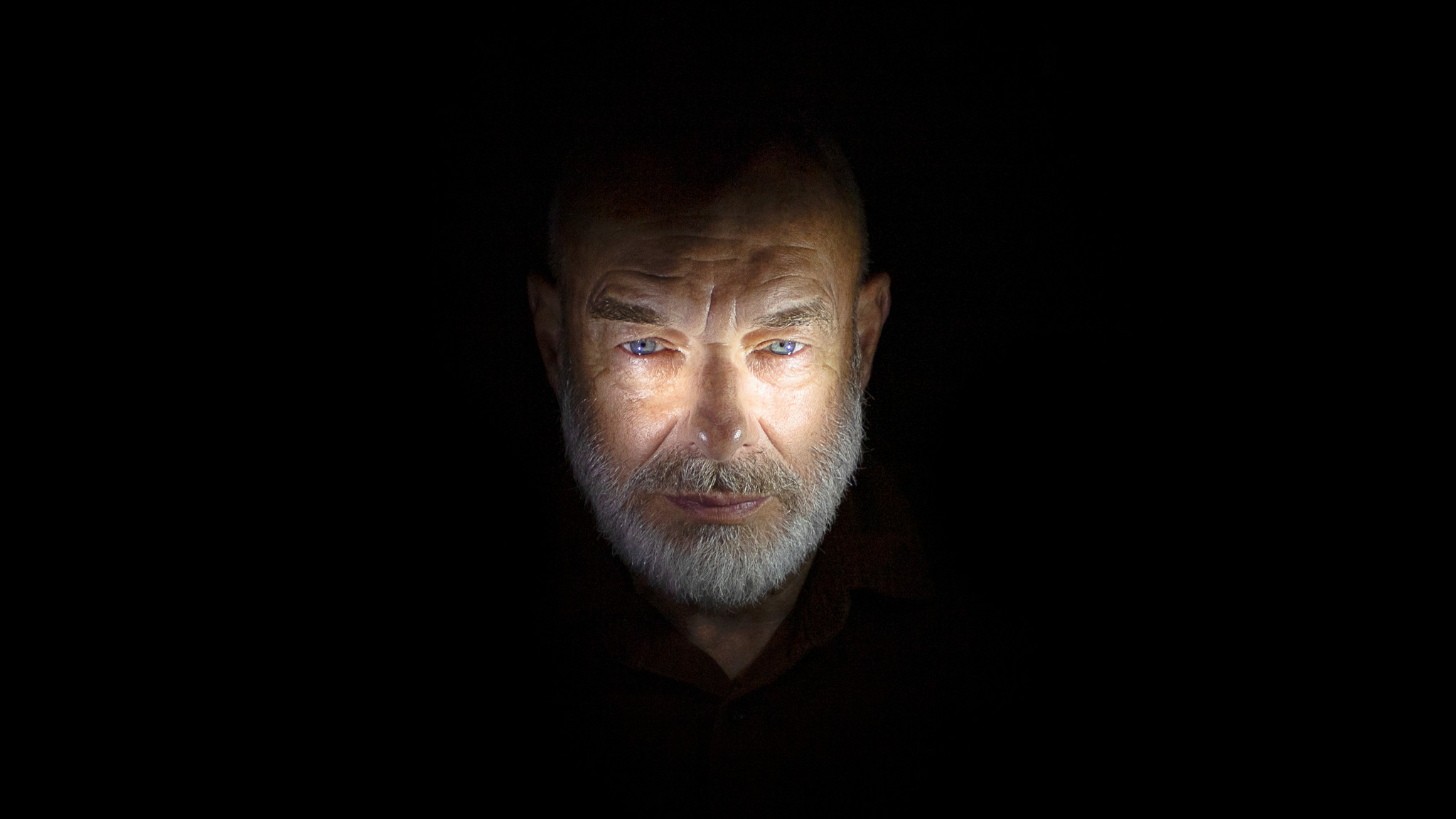

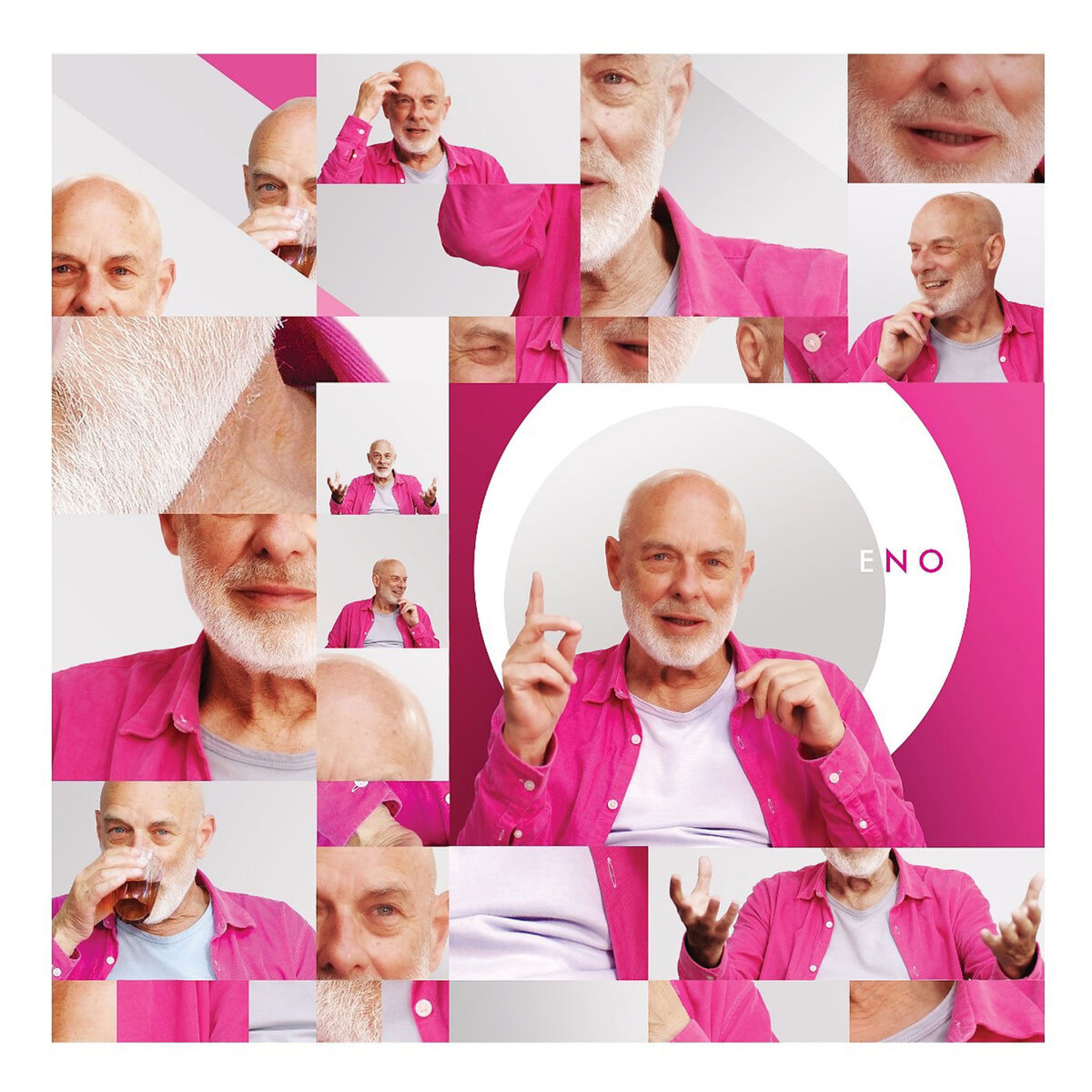

The most widespread definition of ambient music comes from Brian Eno, arguably the inventor – or at least one of the great early innovators – of the genre.

In the liner notes of his 1978 album, “Ambient 1: Music for Airports”, which famously christened the genre, he included a vague definition, the famous line about ambient music being “as ignorable as interesting” and creating “a space to think”.

The French ambient composer Félicia Atkinson comes up with a slightly more tangible definition. Talking about jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders’ 1971 tune “Astral Traveling”, she says:

“(…) this intro says a lot of what’s going to happen in music in the fifty years after. The rise of ambient, house music, trip hop, electronic music – there is this idea of building a landscape with instruments and sounds and electronics, that is very visionary.”

While that might sound very broad too, isn’t “building a landscape with instruments and sounds and electronics” what ambient is really about?

While ambient music – as we know it today – was created in the mid- to late 1970s, you can trace its roots much further back in time.

The writer, musician and academic David Toop does it in his stunning book on the genre, “Ocean of Sound”. Matter of fact, Toop refers to ambient not even as a genre, but as a “way of listening”.

In search of the cultural roots of that approach, he’s going back to French composers from the early 20th century, like Claude Débussy and Erik Satie (whose concept of ‘furniture music’ inspired Eno), and to traditional Indonesian Gamelan and Buddhist ceremonial chants. Creating his 1975 drone piece “Discreet Music”, Eno was also influenced by 18th century harp music, which he reportedly listened to on very low volume while recovering from a severe accident in a hospital bed.

And while “Ambient 1: Music for Airports” is often considered the first real ambient music album, many will argue the drifting instrumental guitar drones of “Discreet Music” already contained the genre blueprint.

Eno was good at branding his innovations, but of course they didn’t happen in a silo. They were inspired by then recent developments in jazz, rock, early electronic music, and avant-garde composition.

One of the songs that would shape his idea of ambient music was Miles Davis’ “He Loved Him Madly”. That piece, a 33-minute tribute to Duke Ellington recorded in 1974, does something remarkable for the time – it conjures a sound landscape. Ambient music? Maybe, if more in the literal sense. Definitely a piece of longform instrumental music that creates an atmosphere instead of telling an actual story.

Miles Davis’ music from his electric period was generally way ahead of its time. Starting with 1969’s “In a Silent Way”, he brought a group of young players to the studio to create a new type of jazz openly influenced by funk, rock and even Indian classical music. Among them were Chick Corea, John McLaughlin and Joe Zawinul, and producer Teo Macero would edit tracks from hours of their improvised sessions.

That style, dubbed jazz fusion, would produce a number of tunes that could be called ‘proto-ambient’. You will find them not only on Miles’ records, but on albums from that era by his players’ own bands, like Joe Zawinul’s Weather Report, John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi group and Chick Corea’s Return To Forever – who in 1972 recorded “Crystal Silence”, one of the ultimate proto-ambient anthems.

This is not about the music being drumless (which it mostly isn’t), but about emphasizing atmosphere, texture and tone over structure, harmony and melody. In the words of Eno biographer David Sheppard, it was “music whose sonic atmosphere outweighed its narrative thrust”.

In classical music as well, new compositional forms had emerged in the 1960s. Musique concrète and minimal music worked with tape loops and field recordings; composers like Éliane Radigue, Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley and Steve Reich wrote pieces entirely consisting of drones and samples, abandoning the traditional focus on melody, harmony and rhythm. In academic music theory, the idea of the ‘soundscape’ emerged, formulated by the composer R. Murray Schafer.

The late 1960s brought elemental change within popular and academic music that resonated well into the 1970s. Composers and artists wrote and produced music that was largely instrumental, textural instead of tonal, and focused on longform, atmospheric compositions instead of short, clearly structured songs.

After The Beatles’ John Lennon and The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson had started incorporating these ideas into their music, British progressive rock bands like Pink Floyd and King Crimson went a step further, taking cues from jazz improvisation and avant-garde music. American composers Laurie Spiegel and Suzanne Ciani started writing compositions on synthesizers. In Germany, the school of Kosmische Musik emerged, with early synth experiments by Klaus Schulze, Edgar Froese, and Florian Fricke.

Among these ‘Krautrock’ artists were Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius of Kluster/Cluster and Harmonia, who would collaborate closely with Brian Eno from 1976 to 1978, right before “Music For Airports”. Many argue that Eno lifted a lot of ideas from his German friends. They even released a mutual album in 1977, “Cluster & Eno”, which sounds very ambient from today’s standpoint.

But Eno had actually started similar experiments himself as early as 1973, when he hooked up with King Crimson’s guitarist Robert Fripp. They experimented with tape loops on a reel-to-reel machine, which Fripp then played treated guitar sounds over. Their album “(No Pussyfooting)” got released a year later, just months after Eno had left Roxy Music, preceding “Discreet Music” by two years.

The album consists of two side-long, beatless, meandering pieces with Fripp’s processed guitar floating over loops and drones. “Discreet Music” resulted from one of Eno’s similarly produced backing tracks, which was used for his live shows with Fripp.

But even if all of these developments were undoubtedly important for the birth of ambient music, it was “Ambient 1: Music for Airports” when the genre descriptor was first launched into cultural discourse.

The influential album consisted of four pieces which were based on layered tape loops of piano, vocal and synthesizer music, originally designed as a sound installation to create a calming ambience at an airport terminal.

Back then, Eno clearly made an effort to differentiate his own musical output from other forms of background music, such as Muzak and Easy Listening, which were considered low-brow and often frowned upon.

That discussion would remain relevant throughout the history of ambient music – while some ambient is merely “functional” lean-back music, as you can hear it a lot on streaming playlists based on moods and activities these days, there is surely also a strain of modern composition based on Eno’s innovations that features an artistic value not to be overlooked.

In the next two episodes of this story, we will look at ambient’s development since the late 1970s until today, and give an overview on today’s ambient music scene.

To be continued.