“This is not just music. It’s like a blank canvas, upon which we can paint our emotions, thoughts and stories.”

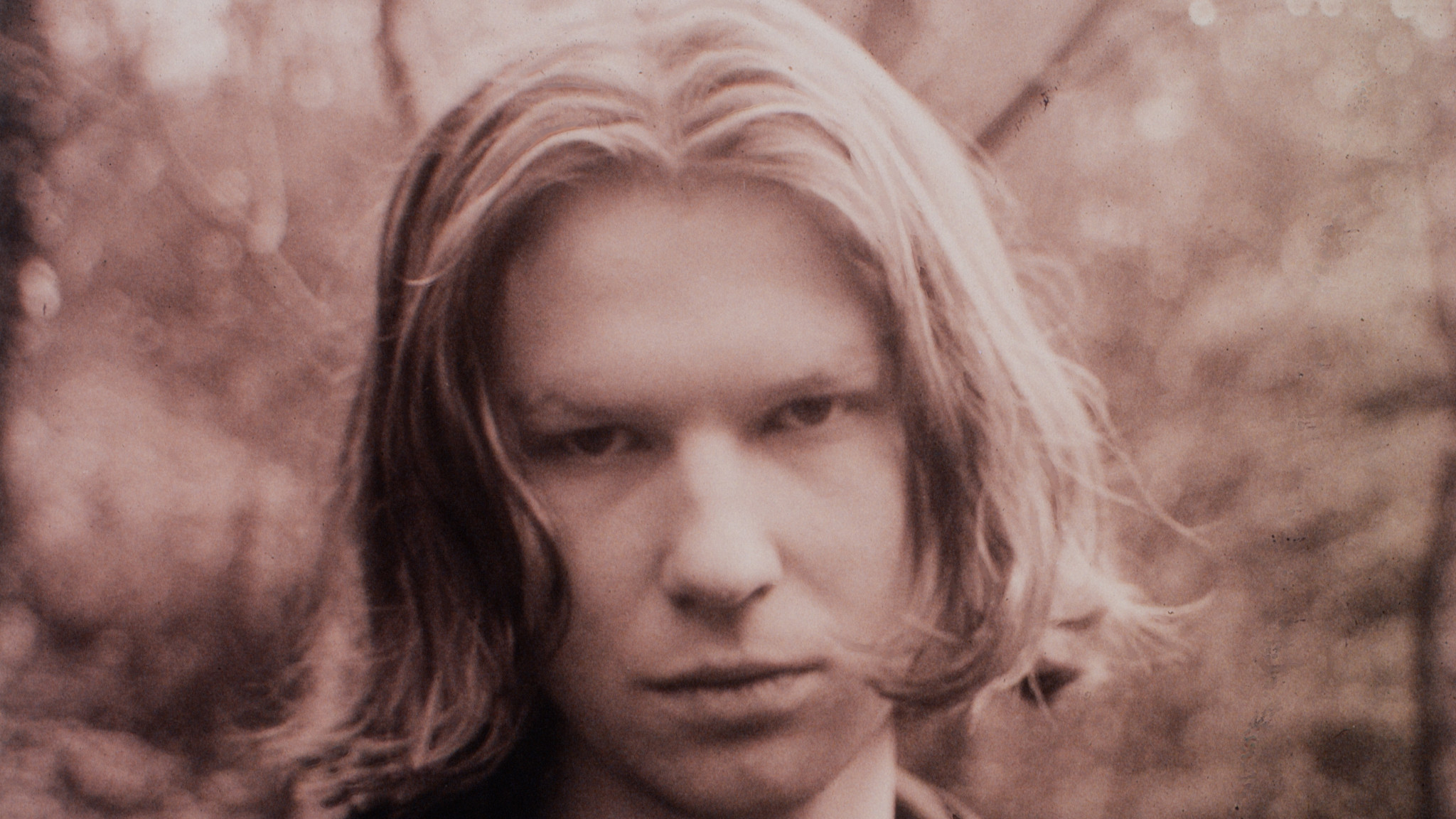

This comment from an anonymous YouTube user might provide an apt definition of all ambient music, but here it specifically relates to the 10-minute instrumental track “Stone in Focus” by the British electronic music producer Richard D. James alias Aphex Twin. It was included on his seminal 1994 album “Selected Ambient Works Vol. II”, often considered one of the true classics of the genre.

On its predecessor “Selected Ambient Works 85-92”, Aphex Twin still had one foot in the club, but now he felt more inspired by minimalist composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich than by fellow techno and house producers. James claims to have written the album in a state of lucid dreaming, likening its sound to “standing in a power station on acid”.

The famous music critic Simon Reynolds once described its tunes as “sound-paintings” and compared its effect to “being inside a dream: not necessarily idyllic, with a strangeness that haunts you long into your waking day.”

As these flowery descriptions show, ambient music is not easy to pin down. A proper definition cannot ever contain an actual formula. Still, certain conventions formed around it as early as the 1980s: Most of it – not all – was instrumental, and most of it – not all – was beatless. These were floating soundscapes without clearly defined song structures, prioritizing texture and atmosphere over harmonic and melodic information.

Today, ambient is often used as a synonym for calm, meditative electronic music. That definition feels too narrow though – most ambient pioneers didn’t prefer either electronic or acoustic sounds. They merged both, and used whatever worked best for their vision.

Brian Eno produced four volumes in his formative Ambient series between 1978 and 1982. While his solo works consisted of tape loops, piano and synthesizer pieces, it’s notable that “The Plateaux of Mirror” and “Day of Radiance” had little to do with what we’d call electronic music today. These albums contained treated and layered recordings of acoustic performances by the late Harold Budd, a classical pianist and composer, and Laraaji, a busking street musician who played a modified zither and a hammered dulcimer.

The early 1980s brought with them new technological possibilities. Musicians didn’t need access to huge studios anymore; they could home-record with portable devices. Electronic instruments and synthesizers made huge leaps in quality and became more affordable at the same time. In this climate, other musicians felt inspired by Eno’s innovations – especially in Japan.

Environmental Music

Early Japanese ambient music went through a recent resurgence in the YouTube era. Back in its heyday, it was a rather niche scene, centering around the Art Vivant record store in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro neighborhood, with composers such as Satoshi Ashikawa, Midori Takada and Hiroshi Yoshimura leading the way.

Their idea was to create serene musical landscapes or sound sculptures; the music was supposed to “float like smoke”. They called their style Kankyō Ongaku, which could be roughly translated to ‘environmental music’ – a term that relates to Erik Satie’s concept of ‘furniture music’ from the early 20th century.

Meanwhile in Europe and the U.S., contemporary classical composers like Éliane Radigue or Pauline Oliveros created sophisticated electroacoustic compositions, building upon what the Minimalists did in the 1960s. Considering them ambient music might feel sacrilegious to purists, but they did experiment with long durations and microtones, ambiguous atmospheres and incremental changes – ideas that were as important to Brian Eno and his Japanese followers.

Around the same time, the jazz scene started engaging with ambient ideas. Building on the foundation of ECM’s romantic chamber jazz – and perhaps slightly trivializing it in the process –, players like the notorious Windham Hill label emerged, releasing a huge amount of fingerpicked solo guitar and other instrumental acoustic music, marketing it as suitable for relaxing, unwinding and meditating.

On the other side of the vibe spectrum, you’d witness a new style referred to as dark ambient. Most of its protagonists came from the burgeoning industrial, goth and dark wave scenes – inspired by pioneering groups such as Throbbing Gristle, Einstürzende Neubauten and Cabaret Voltaire, they created eerie sound collages of deep bass modulations, apocalyptic synth clouds, machine noises and unsettling field recordings. One of their pioneers was the Welsh musician Brian Williams, who performs as Lustmord, but groups like Zoviet France, SPK and Nurse With Wound need to be mentioned as well.

In the 16 years between Brian Eno’s and Aphex Twin’s groundbreaking recordings, ambient went through various stages of acceptance and popularity. On the one hand, it was considered a rising, innovative genre, fueled by a boom in spiritual and esoteric interests often referred to as the “New Age” scene. In other, more elitist circles, the words “Ambient” and “New Age” quickly became insults. In the late 1980s, even Brian Eno didn’t want anything to do with it anymore and temporarily resorted to producing U2 records.

The Big Chillout

The second wave of ambient rose in a countercultural community: the nascent rave scene, where styles like ambient house and ambient techno developed in the early 1990s.

In those days, a new type of conceptual event started spreading in cities like London, Amsterdam or Berlin. For example, London’s legendary Telepathic Fish parties took place in squats or abandoned warehouses. They started at noon, usually on Sunday or a holiday, and went on until the late evening, sometimes the next morning.

DJs like Matt Black, Mixmaster Morris or Alex Paterson played long sets of psychedelic downtempo music. There would be live acts as well – like tribal drummers or didgeridoo players. Space photos and trippy visuals were projected onto screens. While some attendants would engage in free dance, others would just sit down, listen, meditate and zone out. You would run into fire jugglers, Tarot readers and masseurs. Someone might prepare cheese rolls with a Swiss army knife.

In the beginning, just a handful of bleary-eyed ravers showed up to these sit-ins. Soon enough, punks, hippies and art school kids joined them on damp squat mattresses, smoking weed, drinking tea and watching knob-fiddlers hide behind PowerBooks. In his brilliant book on ambient music, “Ocean of Sound”, writer and musician David Toop describes these parties in great detail and talks to some of that scene’s protagonists.

“It’s like being in someone’s living room”, DJ and producer Matt Black told Toop.

The late artist Mira Calix, one of the promoters behind Telepathic Fish, compared it to “people chilling out in their bedrooms – the post-clubbing experience when everyone comes round and you play tunes.”

Designed as calming comedown happenings after substance-fueled techno raves, their wildly experimental DJ sets would move from dub reggae to Berlin School synths to ethereal dreampop to birdsong albums. Electronic music producers had also started merging Eno-like soundscapes with programmed beats in their home studios, creating the foundation of ambient house and ambient techno.

Throughout the 1990s, every rave would have a dedicated “chill-out floor” that often felt inspired by what went down at these early parties. MTV Europe even launched a show dedicated to these specific sounds and visuals: “Chill Out Zone” first appeared in November 1993. German public TV launched “Space Night” in 1994 – conceived to replace the test patterns that ran after the regular TV program ended, the idea behind the cult show was simple, setting images from NASA space shuttle cameras to atmospheric ambient music.

The long-running show provided the backdrop for countless afterparties.

The 1990s in general saw a huge boom in “chill-out music”, clearly influenced by the ambient movement. In places like Ibiza’s Café del Mar, ambient house and techno were played alongside trip-hop, atmospheric drum’n’bass, progressive trance and downtempo grooves to soundtrack the daily sundown.

Umbrella compilations like “Pure Moods” would become wildly popular with a mix containing Jean-Michel Jarre’s synthesizer pieces, Enya’s modern Celtic songs and Enigma’s medieval worldbeat. Acts like Massive Attack, Air or Kruder & Dorfmeister were able to capitalize off of the “chill-out” trend in the late 1990s, selling hundreds of thousands of records.

That trend died down a couple of years later. But the new millennium spawned new trends in electronic music that would clearly draw from ambient again: One of them would be neoclassical music.

The original ambient sound, as designed by Brian Eno and developed further by Aphex Twin, might have been driven to the margins. But the ideas behind ambient music were now everywhere – they had infiltrated popular culture to a degree neither Eno nor James could have imagined.

In Part 3, we’ll look more deeply at the third ambient boom of the 2010s, the implications of the streaming model on the genre, and the contemporary “ambient/experimental” scene.

Words by Stephan Kunze